‘Airborne’ seems to be the hardest word

UK POLITICS: Why do UK Infection Prevention and Control guidelines still not acknowledge airborne transmission of Covid-19?

by Anne Marie McConway, North West Bylines

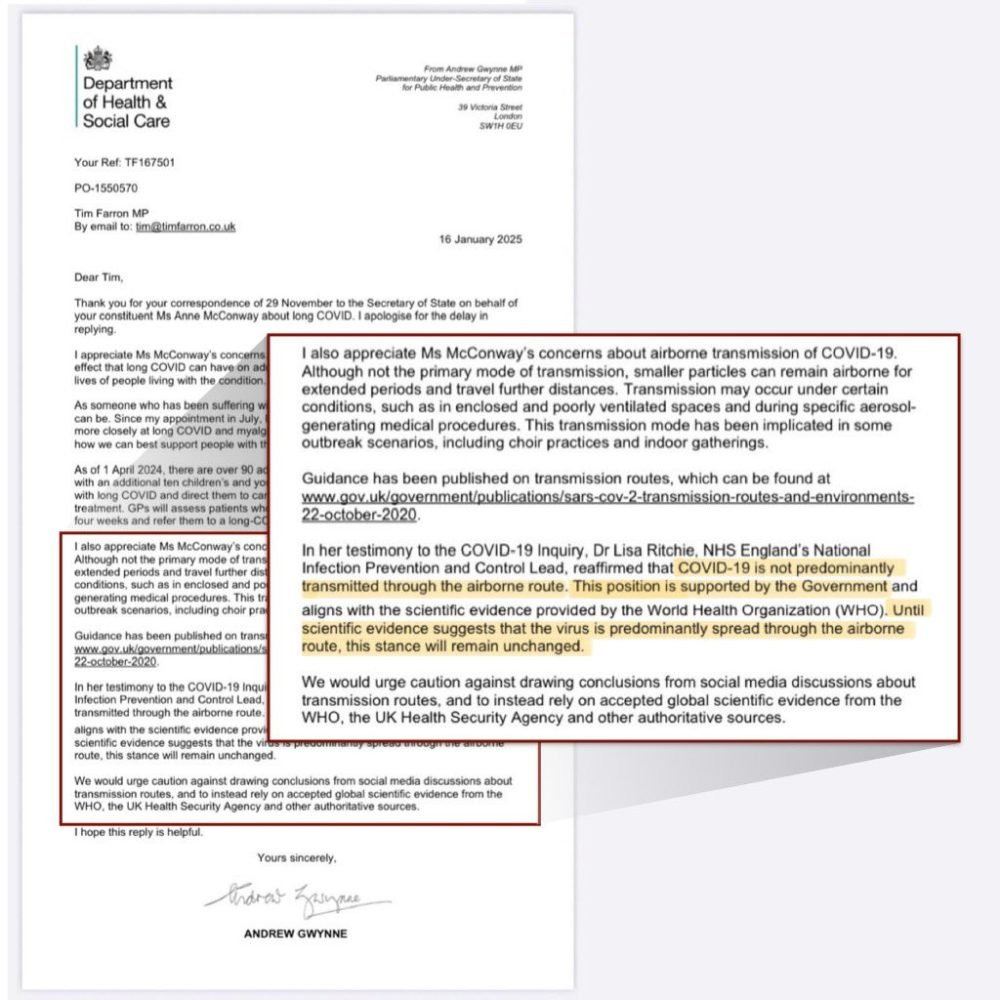

A letter sent recently by Andrew Gwynne – the parliamentary under-secretary of state for public health and prevention – has sparked serious concerns regarding current UK Infection Protection and Control (IPC) guidance.Tim Farron – the MP for Westmorland and Lonsdale – asked a question on behalf of a constituent about the lack of airborne mitigations in healthcare settings and schools. In his response, Gwynne unexpectedly doubled down on the widely criticised position put forward at the Covid Inquiry by Dr Lisa Ritchie, the Head of IPC. See a short video clip of an awkward exchange during Dr Ritchie’s testimony here. The government’s stance does not acknowledge the need to mitigate against the airborne spread of Covid-19.

Is Covid-19 spread ‘predominantly’ via the airborne route?

According to most experts who gave evidence at Module 3 of the Covid Inquiry, the answer is ‘yes’. Yes, it is. One such example is the testimony given by Professor Clive Beggs which you can see a video clip of here.

“The bulk of the virus is in the smaller aerosols not in the big droplets, that is the evidence now. That goes for both Influenza and Covid.”

The argument put forward by the government, to justify the lack of airborne mitigations, is that Covid-19 is not ‘predominantly’ spread via the airborne route; they maintain that the ‘predominant’ mode of spread is through droplets and contact. This position now goes against the latest science. The evidence cited to support this inaccurate position by Gwynne in his recent letter was outdated, debunked World Health Organization (WHO) guidance from 2020.

Moreover, only mitigating against the perceived predominant route of transmission is not how we deal with other infectious diseases. The predominant route of transmission for HIV, for example, is sexual intercourse, but we still prevent it transmitting through blood. What is more, the National Infection Prevention and Control Manual makes no mention of the word ‘predominant’ at all. It clearly states that:

“Respiratory protective equipment must be considered when a patient is admitted with a disease spread WHOLLY or PARTLY by the airborne route.”

The first report published from the Covid Inquiry has already concluded that the previous Conservative government “failed its citizens” due to a culture of “groupthink” where ministers failed to challenge the advice they received here. It would appear that this ‘groupthink’ culture persists under the new Labour leadership.

More recent WHO guidance has emphasised the significance of airborne transmission of Covid-19. Furthermore, when she was questioned about airborne transmission at the Covid Inquiry, the head of the UK Health Security Agency, Dame Jenny Harries, said:

“I think everyone now accepts that it’s there and is significantly higher than was accounted for at the start.”

So, in light of the new scientific information, why aren’t the government protecting people now?

Why doesn’t the government just update the IPC guidance?

Perhaps the most obvious answer to this question is that Covid-19 prevention is no longer a vote winner. Talking about and investing in protective measures to reduce the spread of Covid-19 is unlikely to be politically advantageous, so our politicians are no longer motivated to act. This is despite the fact that introducing airborne mitigations (such as upgraded ventilation and air filters) in healthcare settings and schools, for example, would reduce the spread of ALL airborne pathogens including Covid-19, influenza, whooping cough, RSV and measles (to name a few). This would, in turn, ease the pressure on our overstretched, under-resourced NHS.

In her testimony at the Covid Inquiry, Professor Cath Noakes suggested some other possible explanations for the apparent reluctance to amend IPC guidance such as: the difficulty and cost of implementation; a reluctance to make institutions responsible for protecting people (as opposed to the individual); and not wanting to frighten the public by stating openly that infectious airborne particles are in the air we breathe.

Liability is also likely to be a major consideration. Admitting that airborne mitigations were/are required could open the floodgates for compensation claims from workers and their families who have lost loved ones or suffered long-term health problems due to inadequate protective measures.

Nevertheless, whatever the obstacles may be, governments shouldn’t be allowed to just pick and choose which routes of transmission are the easiest and cheapest to deal with, should they?

Reactions to Gwynne’s letter

Many in the scientific community have been shocked by Andrew Gwynne’s response. Dr Allen Haddrell, an aerosol scientist at Bristol University, was on his way to a dinner to celebrate the end of a five-year project exploring airborne transmission of Covid-19, when he saw Gwynne’s letter on social media. He said:

“Why are we doing all of this research if they are just going to ignore it? When I shared the letter with others on the team, it got a little awkward…”

Four of the largest long Covid groups have also jointly instructed their legal representatives to respond publicly to Gwynne’s letter. They highlight the ample evidence provided by multiple expert witnesses at the Covid Inquiry, who stated clearly that Covid-19 is NOT predominantly spread via droplets.

It is also important to note that, over the last five years, the British Medical Association, the Royal College of Nursing and the Covid Airborne Transmission Alliance have all repeatedly written to the government pleading for the IPC guidelines to be updated; all requests have fallen on deaf ears. This is one such letter. To this day, healthcare workers remain inadequately protected; one consequence of which is that one third of NHS healthcare workers now have long Covid symptoms.

Disappointingly, the intransigent government stance and inadequate IPC guidance have not been challenged in the House of Commons by the opposition parties since the Labour Party came to power. Labour has committed to implementing the recommendations of the Covid Inquiry, but these are not likely to be published until late 2026. There is however some hope on the horizon from the Green Party for England and Wales, who have a Covid-19: Long Covid and Clean Air policy, which calls for airborne mitigations, such as improving indoor air quality and reinstating masks in healthcare. Baroness Natalie Bennett, a Green Party peer, recently asked the government how it assesses itself on providing clean indoor air in crucial spaces, including schools, in light of the continuing threat of respiratory viruses. The government reply failed to answer her question.

Can we afford NOT to acknowledge airborne spread?

Contrary to popular belief, as per the WHO website, the Covid-19 pandemic is ongoing and the costs of ignoring it are very high:

In 2024 more than 11,000 deaths in the UK were linked directly to Covid, an average of 200 people per week.

Recent data from Wales found that during the week of 19 January 2025, 74% of patients in hospital with Covid contracted it whilst in hospital.

According to the latest NHS GP-patient survey, an estimated 4.6% of the population now have long Covid, equating to 3.1 million people across the UK.

A report published by The Economist in April 2024 estimated that long Covid would result in more than 251.8 million work hours lost in 2024.

We also know from the ONS survey that instances of long Covid in children have been rising at an alarming rate, nearly DOUBLING in the year ending March 2024, to over 111,000 children in England and Scotland alone.

Between Sept 2023 and April 2024, 1% of ALL babies under six months old had a hospital stay due to a Covid-19 infection; eight of those babies died.

Long Covid ambassador?

Prior to the general election, Gwynne often publicly shared his own health struggles with long Covid. It was anticipated that this lived experience would translate into action. There were high hopes in the long Covid community when he was appointed, as discussed on James O’Brien’s phone-in show on LBC radio. These hopes have been dashed by this letter, and by Gwynne’s near silence about the ongoing harm being caused by the pandemic since coming to power. Without effective infection control measures, Covid-19 will continue to cause significant harm to population health, which will then, of course, affect the economy. Prevention is always better than cure, especially when there is no treatment or cure!

As Gwynne himself said in 2022:

“As night follows day, the more COVID transmission there is, the more Long COVID there will be.”

Future pandemics

Looking to the future, Sir Patrick Vallance has warned that we are certain to face another pandemic. The endless prevarication over the significance of airborne transmission of Covid-19 has meant that no action has been taken to improve ventilation and indoor air quality. This is a missed opportunity which leaves us ill-prepared.

Given the pandemic potential of bird flu, and the government’s failure to acknowledge airborne transmission of Covid-19, many are understandably worried by the current government advice, which also makes no mention of bird flu spreading via the airborne route. Unlike the public health advice in the US, Canada and mainland Europe which clearly warns citizens that bird flu can spread through airborne transmission.

We MUST learn from our mistakes, otherwise we risk repeating them.