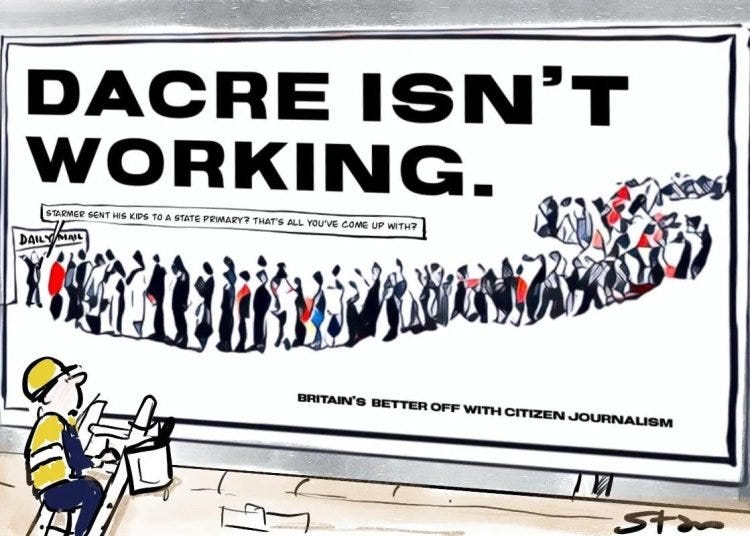

Britain’s better off with citizen journalism

From lockdowns to letdowns, five years on Anthony Robinson reflects on Brexit, citizen journalism, and a nation still adrift

by Anthony Robinson, Yorkshire Bylines

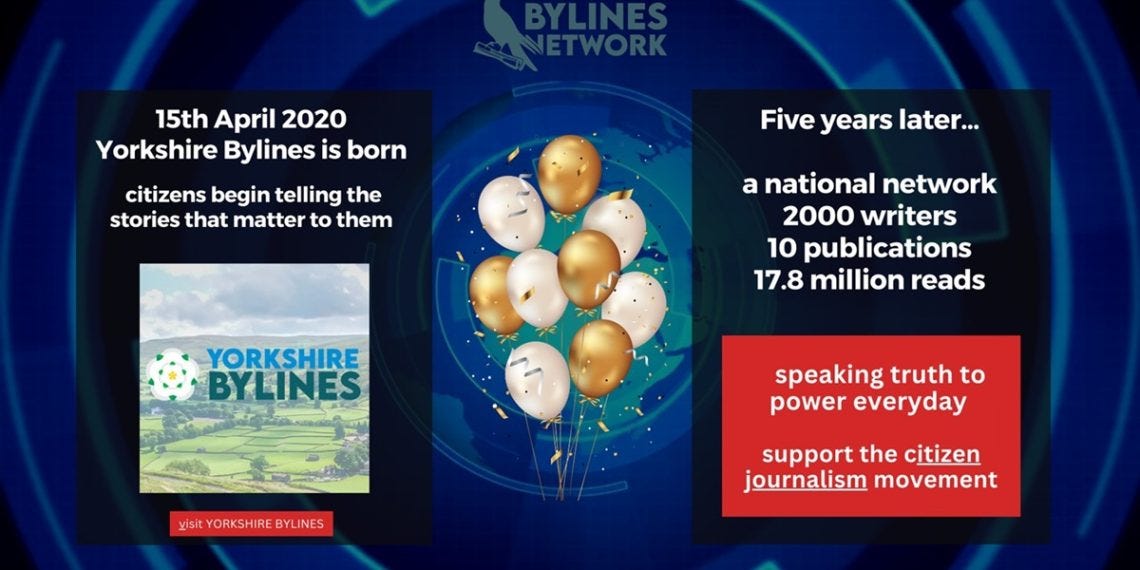

Today’s world is barely recognisable from the one that Yorkshire Bylines launched itself into in mid-April 2020. Britain had formally left the European Union and was in a transition period beginning talks to agree a new trading relationship. The nation was under lockdown to protect us from a global pandemic from which we had no immunity. Donald Trump was in the final year of his first term as president of the USA.

A few weeks earlier, newly elected PM Boris Johnson had dismissed warnings about coronavirus saying it could “trigger a panic” that would cause “real and unnecessary economic damage” by “going beyond” what was “medically rational”.

On 19 March, he suggested the UK could “turn the tide” of coronavirus in 12 weeks. Four days later he ordered people to stay at home. And so we did, beavering away on our keyboards and learning the intricacies and etiquette of Zoom as we embarked on what then seemed like a high-wire experiment in citizen journalism.

None of us were proper hacks, even novice ones, or knew our way around the back end of a WordPress website, but we somehow muddled through together with help and advice from the team at Byline Times who provided technical and moral support. We finally went live on 15 April.

The Bylines Network has now expanded to allow hundreds of writers, all unpaid, to publish interesting and professional looking articles every week across two national and eight regional publications, all with their distinct identities. I am proud that we seem to have started something that has given a platform to all kinds of people, like me, who had a bee in their bonnet but never thought they could write a serious piece on any topic worthy of publication.

We now have thousands of dedicated readers in this country and worldwide.

Brexit

My contribution to Yorkshire Bylines, over 400 articles now, has generally been about Brexit, something I believed to be a profound mistake that was always bound to negatively impact trade and productivity, with the result inevitably feeding through to government finances.

When tax revenues fall, investment in public services like health, education, welfare, defence and vital infrastructure projects follows in a downward spiral along with faith in politicians and politics more widely. Life for many is made a little harder and less enjoyable. Money isn’t the root of all evil, but the lack of it can be.

I should admit I am no expert in international trade (or anything else for that matter) but I do tend to read a lot of dry reports and I have always tried to amplify the views of people who I think understand these things much better than me, unlike Michael Gove, et al.

I do, however, think I’m entitled to a hearing on British manufacturing, since I worked inside it for half a century and visited countless factories, in many different industries, both here and in Europe. The idea of ‘Global Britain’ succeeding alone always seemed a complete fantasy to me, pedalled by people who occasionally slipped on a hi-vis jacket for a brief photo op.

Red tape and regulations

A topic I’ve returned to again and again is deregulation. One of my first pieces was Brexit’s Great Repeal Mystery about government plans to slash regulations, since I couldn’t see how this could ever be realistically accomplished. Apart from cutting trivial, out-of-date, and irrelevant EU laws, governments of both colours have done little except achieve the worst of all worlds.

We are out of the single market but still following the vast majority of the acquis communautaire.

Divergence is happening, but by accident. The Labour government isn’t looking to ditch more EU rules, while the EU is busy making new ones, which MPs never see and don’t debate. We are simply being left behind. This is the so-called ‘Brussels effect’ where countries outside the EU voluntarily follow EU laws – something else I’ve written about – simply because of self-interest. It makes economic, legal, technical or environmental sense to maintain European standards, which will also help prevent Britain becoming the Singapore-on-Thames beloved of Brexiters.

I expect little change in the foreseeable future. People generally like regulations. They want fair employment and consumer protection rights and they care about the environment. Plus, Johnson agreed, probably unwittingly, under the trade and cooperation agreement not to reduce the overall level of labour and social protection in a way that impacts trade or investment.

At the moment, we are simply adrift, not moving far from safe harbours in Europe, or showing any ambition or ability to embark on any ‘great voyage’ as a free trade champion. Meanwhile the world collapses into protectionism under Trump.

Productivity

During management training years ago, we were taught that you can relatively easily add to an employee’s knowledge or train them in a skill. Far more difficult to change is someone’s attitude. This, in my opinion, is at the heart of Britain’s long-standing productivity problem, from the boardroom to the shop floor.

Forget tweaks to tax levels, or even industrial policy; they might help at the margins but politicians have attempted all this sort of stuff over decades with no sign of success.

When I first started to work with continental manufacturers, it was clear to me that attitude was what was different about their approach to manufacturing. Engineers were far more dedicated and more innovative; workers actually believed in what they did and were far more serious and diligent; managers more knowledgeable and willing to listen to new ideas or accept criticism.

CEOs’ willingness to invest larger sums for longer periods before a payback came from trust in the workforce’s ability to deliver. Above all, there was a constant push to improve product quality and reliability.

Britain also has world-class businesses, we just don’t have enough of them, which is why I have written about our woeful record of investment in robotics.

Northern Ireland

Another subject I’ve covered is Northern Ireland. Nowhere are the malign impacts of Brexit being seen more clearly than in the growing division between that nation and Great Britain. This is the sea border that Johnson once denied would ever exist. It is now a permanent memorial to the folly of Brexit.

Only last week the Northern Ireland Assembly’s EU Affairs Team (think about that one) issued a newsletter setting out various issues related to having a foot in two different camps.

Stakeholders were invited to write to Lord Murphy of Torfaen who is preparing an independent report for the UK government on the operation of the Windsor framework, Rishi Sunak’s revised Northern Ireland protocol. There is growing pressure to get a sanitary and phytosanitary agreement with GB – that is within our own country – to ease ‘border’ friction.

Other issues included horticultural products, fishing negotiations, eco-design regulations, trade with the USA, and the EU’s artificial intelligence framework. Even the Royal Mail have new rules that take effect from 1 May under the Windsor framework.

There is a whole industry, with all the attendant burden, now set up to manage the red tape created by Brexit for trade inside our own borders! It is complete madness.

Austerity

In 2020, as lockdown got underway and the government announced its job retention scheme, funding 80% of the salary of workers who risked being laid off, I wrote that the period of austerity we had been through for the previous decade after the financial crash, would continue for another 10 years, exacerbated by both Brexit and the pandemic.

Sadly, that has proved to be true. Living standards have stagnated, food bank use has soared and satisfaction with the NHS has reached new lows. Five years on, the new Labour government is still looking for further cuts to public spending.

More than half of Britons think the country is either heading back into austerity or has never left it, according to a report from the think-tank More in Common.

David Davis

I instigated and maintained the Davis Downside Dossier to remind us all that the then Brexit minister, speaking from the Commons despatch box in October 2016, had cockily boasted: “there will be no downside to Brexit at all, and considerable upsides.” As in so many things, Davis was to prove himself spectacularly wrong.

The dossier hit 2,000 entries in September last year when I decided the point had been hammered to death and I stopped adding to it. That isn’t to say there are no more downsides. They continue to pile up at about the same rate.

The dossier seems superfluous now. It is widely accepted that Brexit hasn’t delivered what was promised. Only 11% believe it has been more of a success than a failure. Over a range of areas, from international trade to crime and the cost of living, the overwhelming majority now accept Brexit has either had no impact at all, or a fairly or very negative one.

As we look forward to the next five years, I am quite confident that Britain in 2030 will be even closer to rejoining the European Union. And, assuming I’m still here, I hope to keep spreading the word in my own small way.